Turning the database inside out again

How Kafka and Iceberg are rebuilding database primitives. indexing, caching, and deduplication outside the database engine.

Over a decade ago Martin Kleppmann predicted we’d turn the database inside out and that Kafka would be in the middle of it.

https://martin.kleppmann.com/2015/03/04/turning-the-database-inside-out.html

Modern enterprises that embraced event streaming have essentially turned their monolithic databases inside out into distributed components that resemble a database when looked at holistically. Martin was right but Kafka is not the only star. Open table formats are the turning point where we finally turned the database inside out - they allow organizations to build their own Snowflake.

Martin talked about 4 things:

Log Replication

Materialized Views

Secondary Indexes

Caching

Of these four, two of them (Replication and Materialized Views), have successfully transitioned from internal database implementation to external core components of stream processing:

Kafka and the rise of event streaming has featured ingestion of events into an externally, durably-replicated facing log

Materialisation of these events in a downstream view (e.g. state in Streams/Flink or DB tables via Kafka Connect).

But what about the other two? It’s been rare to hear about secondary indexes or caching in our day to day life as event streaming developers. These remain opaque, duplicated and fragmented inside the downstream systems fed by event streams.

For instance, it was not until you materialized a stream into e.g. Postgres that you could apply indexes and perform fast point lookups on it.

Streaming pipelines generate immense volumes of immutable data, but ad-hoc querying or joining across that data efficiently remains practically impossible due to a lack of secondary indexes.

Similarly, from the beginning caching was crucial for performance when data was repeatedly accessed and transformed. Kafka had basic caching inside it but nothing for external systems which required format conversion. For example, in retail cases transactions data was landed into Kafka. This data was then transformed and loaded into Logistics (for stock levels) and Marketing (for recommendations) domains via Connect. A cache avoided the two flows processing the same data in the same way twice (why burn that extra cpu?).

What’s more, turning the database inside out didn’t stop with Kafka. With the advent of open table formats such as Apache Iceberg more and more of data storage and processing internals were exposed. Iceberg exposed previously internal concepts like partitioning, versioning, logical deletion and statistics to allow processing engines to work with data at previously impossible levels of flexibility and performance.

In this article I’m going to explore these database concepts (and more) through the lens of Kafka and Iceberg to challenge how we think about the boundary between streaming systems and data lakes and how Iceberg might just be the bridge that finally unites them.

Part 1: Exposing the WAL again

Inside a modern database, new data is written to a Write-Ahead Log (WAL) before being persisted to long-term storage (like a diary the database keeps, noting down everything that happens so it can retrace its steps if needed). A decade ago, Martin Kleppmann championed the idea of making the WAL externally visible, streaming it through systems like Kafka, while pushing long-term storage into lakes via ETL such as Kafka Connect.

This separation unlocked real-time architectures, but it also created a new problem: Data became split into a hotset (WAL) and a coldset (data lake), and recombining them became the application’s burden.

A database owns both layers and so can seamlessly merge “just-written bytes” from the WAL with “years-old pages” on disk and present them as one coherent table

Caching, buffer pools etc. make this fast and transparent. But once we turn the database inside out, we lose this built-in functionality.

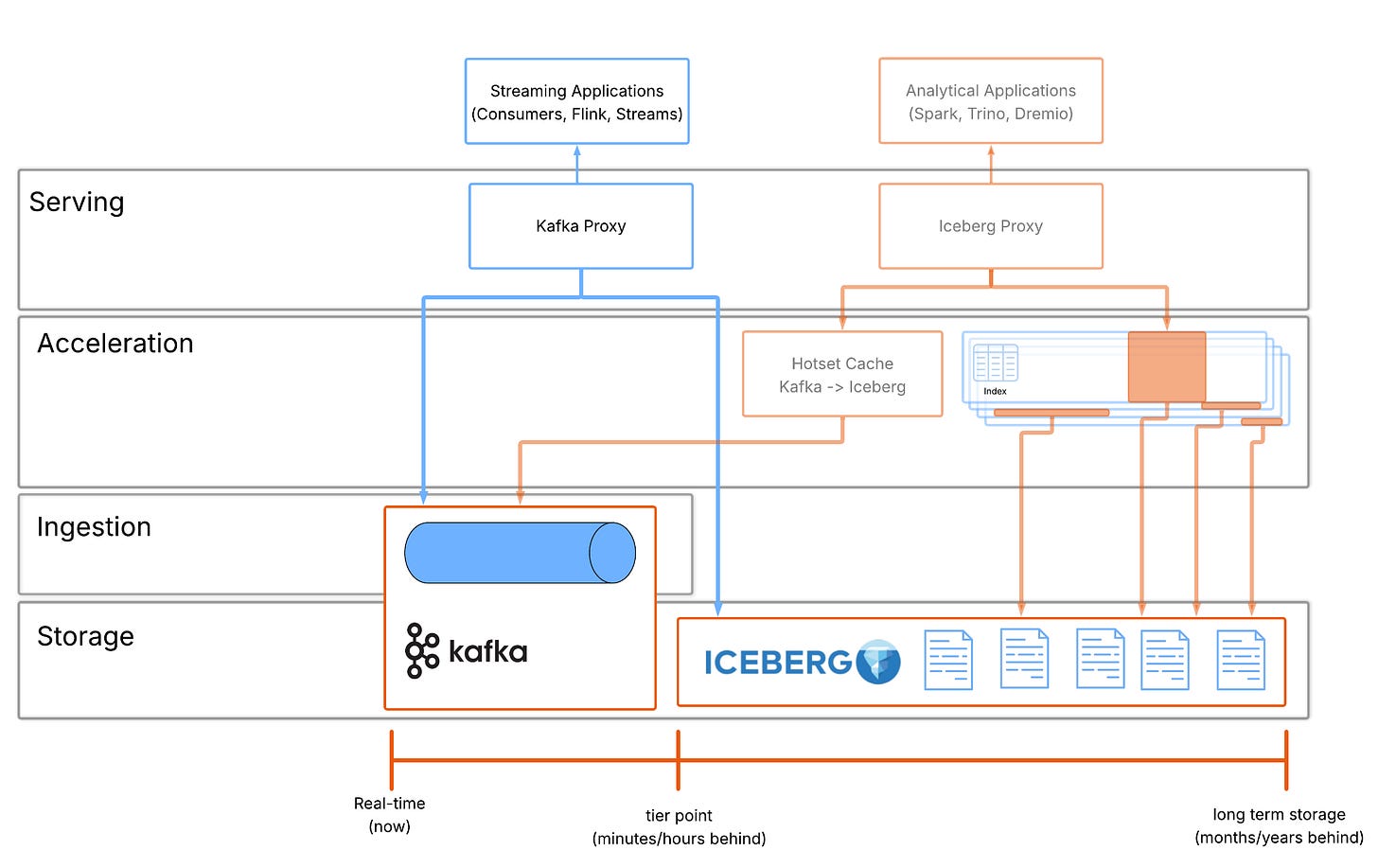

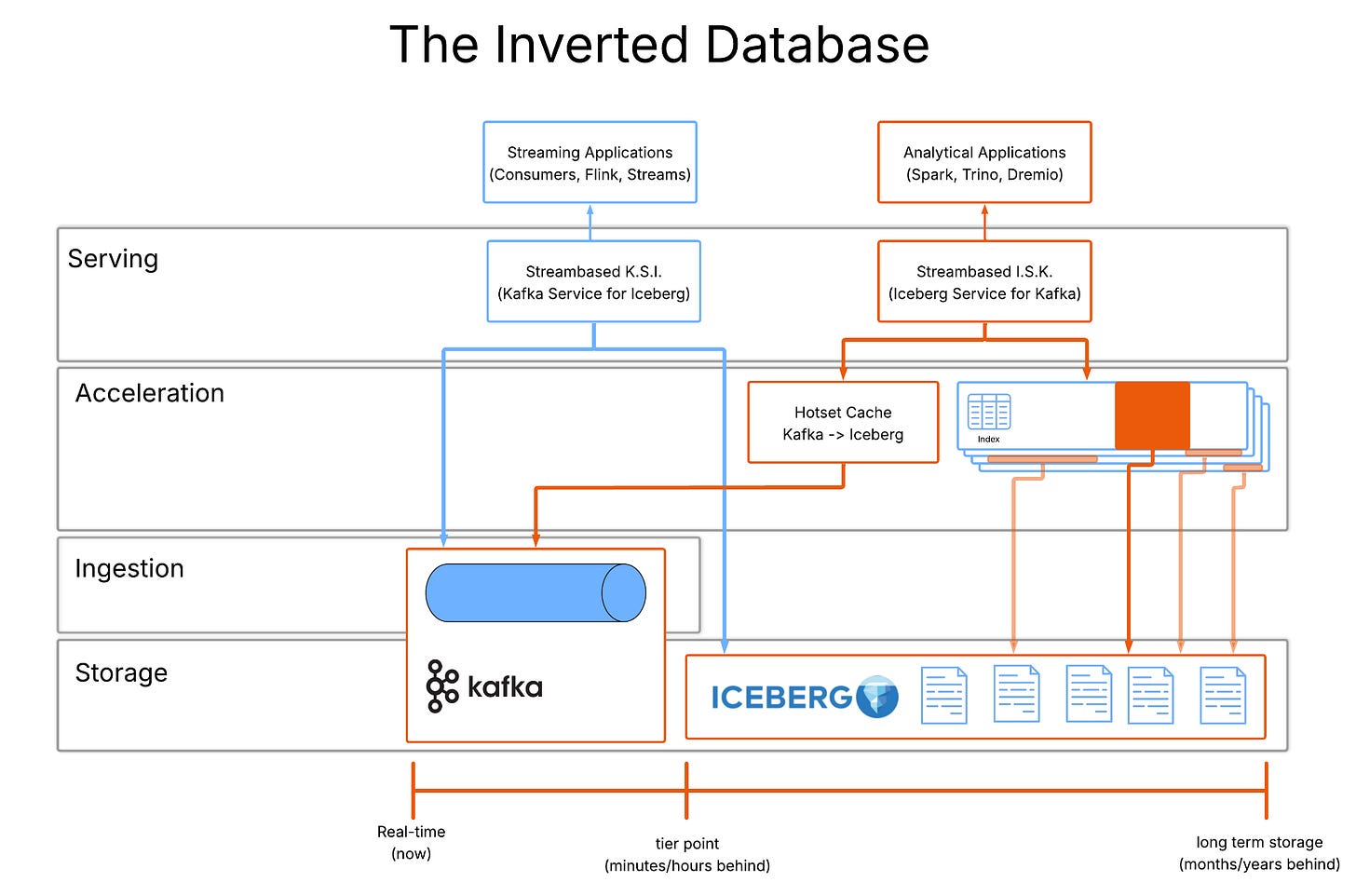

In the inverted architecture, Kafka becomes the WAL and as such is a short term buffer into more permanent storage. Kafka was never designed for long retention and keeping large retention windows is expensive and impractical.

For the long-term storage destination, the answer today is clear: Apache Iceberg

It provides:

Cheap durable object storage

More complex access patterns (SQL)

Schema and partition evolution

Unfortunately, streaming ingestion into Iceberg causes unmanageable metadata explosion.

Fundamentally, the WAL (Kafka) and the lake (Iceberg) speak different languages, records vs. files, offsets vs. snapshots. Each is highly attuned to it’s specific role.

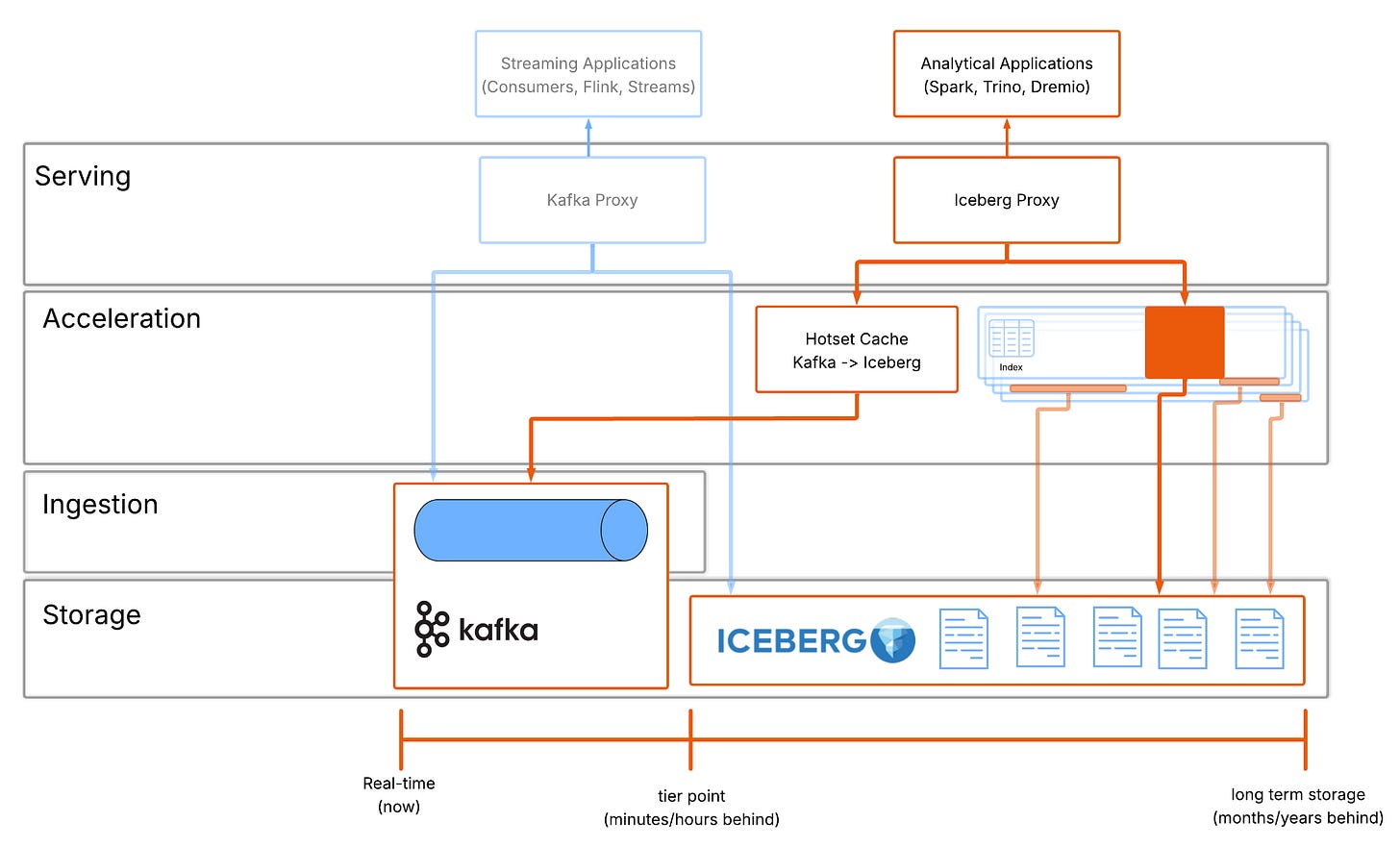

The missing piece: a layer that projects Kafka into Iceberg. We call this Streambased I.S.K. (Iceberg Service for Kafka). I.S.K. is a database-like fusion of WAL+ long term storage, that functions as a cache above Kafka that:

Mirrors the structure of Iceberg tables, not the structure of Kafka topics

Presents the hottest window of data remaining in Kafka + cold data already in Iceberg

Dynamically translates Kafka records into Iceberg-shaped files/metadata

This allows Iceberg clients to see one logical table, clients query a single table but under the hood, the cache is doing the work of DB internals.

“But Kafka already caches data!”

Yes, Kafka relies heavily on the Linux page cache. This is what makes it fast for consumers: recent reads and writes are served directly from memory.

But this cache:

Is accidental, not controlled

Is record-oriented, not table-oriented

Does not mirror the layout or semantics of Iceberg tables

Great for stream consumption, but not the caching layer you need to unify stream+lake data.

A true “inverted database” needs more than a visible WAL and scalable lake storage, it needs a caching layer that reassembles them into a single, coherent table the way a traditional database always has.

Part 2: Indexing

Does Kafka have indexes?

I asked this question in a recent talk at Confluent’s Current Conference and only 2 thought it did. Even engineers that have worked on Kafka for years aren’t aware of Kafka’s built in indexing.

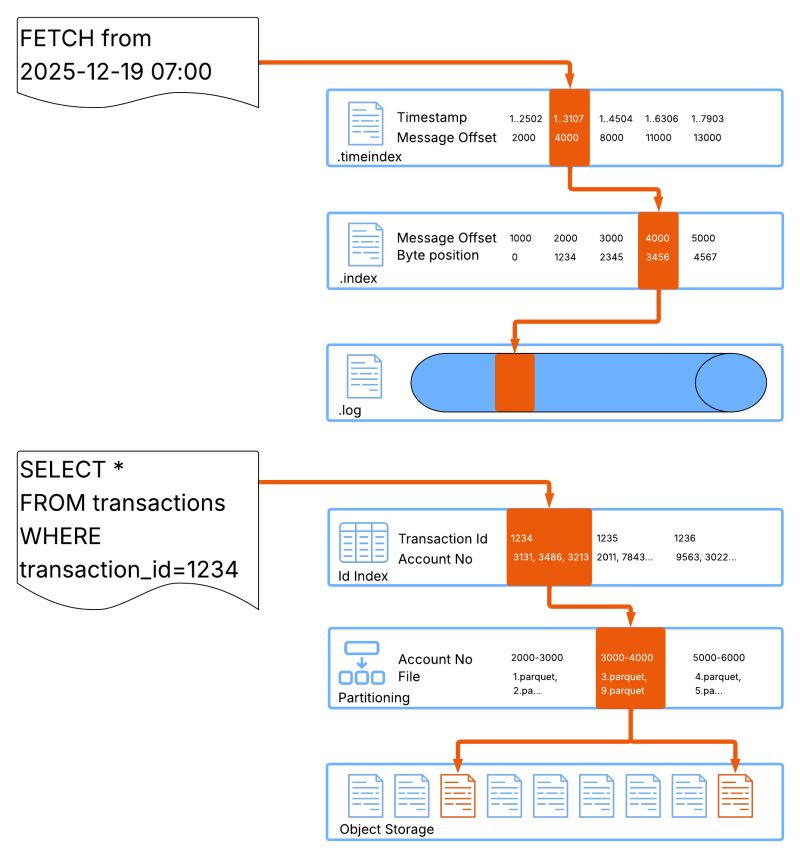

Kafka actually maintains two indexes:

An offset index maps message offsets to physical byte positions in the Kafka data files - this index is used to quickly find the correct position in the data to read from.

A time index maps message timestamps to message offsets - this allows you to seek a particular time in a topic quickly and easily.

Don’t take my word for it, if you open the data directory in your Kafka cluster you will see files ending “.index” and “.timeindex” alongside the log data.

These indexes don’t physically reorder data to answer queries faster. Instead, they layer lightweight additional structures that map question (“what happened at time x”) onto the original data layout.

The same idea can be applied in Iceberg where data is physically laid out in partitions. A partition is a collection of data files that share common attributes. For instance, partitioning may group financial transactions by account no., making it faster to calculate the balance for an account.

Unfortunately, because partitioning affects the physical data layout, it’s difficult to optimise for multiple query patterns. If we wanted to search our financial data by transaction id, partitioning by account doesn’t help and the engine would need to visit every account partition to find the correct data.

We can address this problem in the same way Kafka addresses querying by timestamp: by layering indexes on top of each other to resolve the correct data. With a new index that maps transaction id -> account no.. our Iceberg engine can lookup by transaction id with the same performance boost as if it was looking up by account no. The flow is this:

Find the transaction id in the index and find the account no(s) associated

Query the table for the account no. pruning away unneeded partitions

Filter the (much smaller) result set for the transaction id.

Iceberg already provides the tools for this. An Iceberg table is the ideal place to store the index and applying the index is a case of adjusting the query:

SELECT *

FROM transactions_by_account_no tab

JOIN transaction_id_to_account_no index

ON tab.account_no = index.account_no

WHERE index.transaction_id = ‘1234’Given the above, Iceberg engines (Spark/Trino etc.) are able to follow the join and execute the query faster.

The principle is the same, Kafka translates timestamps → offsets → bytes; Iceberg translates predicates → partitions → files, both without changing the layout.

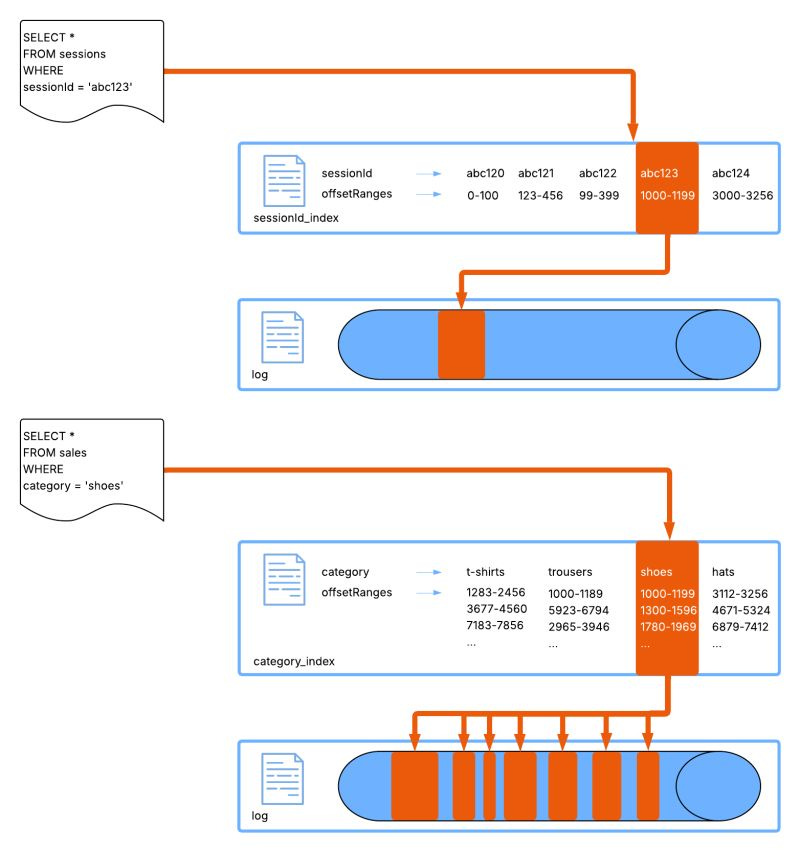

This is not a silver bullet however, for translation layers to work well the data it is addressing should be naturally-clustered (spoiler alert: a LOT of data is naturally clustered) and high cardinality. Timestamps are a great example of this, in most cases Kafka data is roughly time ordered anyway, we can expect records to be loosely clustered by timestamp but because we cannot guarantee this, selecting a time range in Kafka without an index involves a full scan. Kafka’s time index takes advantage of this naturally clustered layout to quickly find the clusters we are interested in and save a lot of scanning.

Another great example is a sessionId. Sessions are generally short-lived, so you have high certainty that events for a given session are grouped close together. This means:

An index on sessionId allows lookups to jump to a small contiguous region(s)

Reads on the underlying data stay mostly sequential and cheap

A predictable, bounded amount of data to read per session regardless of total topic size

That last point is important because it highlights why this scales: the cost of the lookup grows with the session size not with the log size.

You see the same pattern with request IDs, trace IDs, transaction IDs, common fields that already have great locality.

Not all data can leverage translation layers though. Consider something like a product category: A low cardinality field that would usually be evenly spread across the entire offset range. If we apply our translation technique here we end up with the following roadblocks:

Every value maps to offsets across the entire topic

Index lookups fan out into many small, non-sequential reads

The end result is close to a full scan of the underlying data

Instead of looking closer at the data, we often reach for practices that expensively rewrite the underlying data (repartitioning, compaction etc.) or move it to entirely new storage layers. All the while ignoring the fact that the existing layout could already support fast access with a thin translation layer on top. This is what we’re building in Streambased.

Part 3: Too much indexing

In the previous section we talked about what’s possible with indexing via translation structures. However, in data streaming today, indexing typically means materialisation of events into a state store. From this separate store, streaming data is read, re-organised and stored duplicately in a layout more suitable for access by future operations. For instance, taking a stream of financial transactions and using them to construct a table that is organised by the account number the transaction relates to.

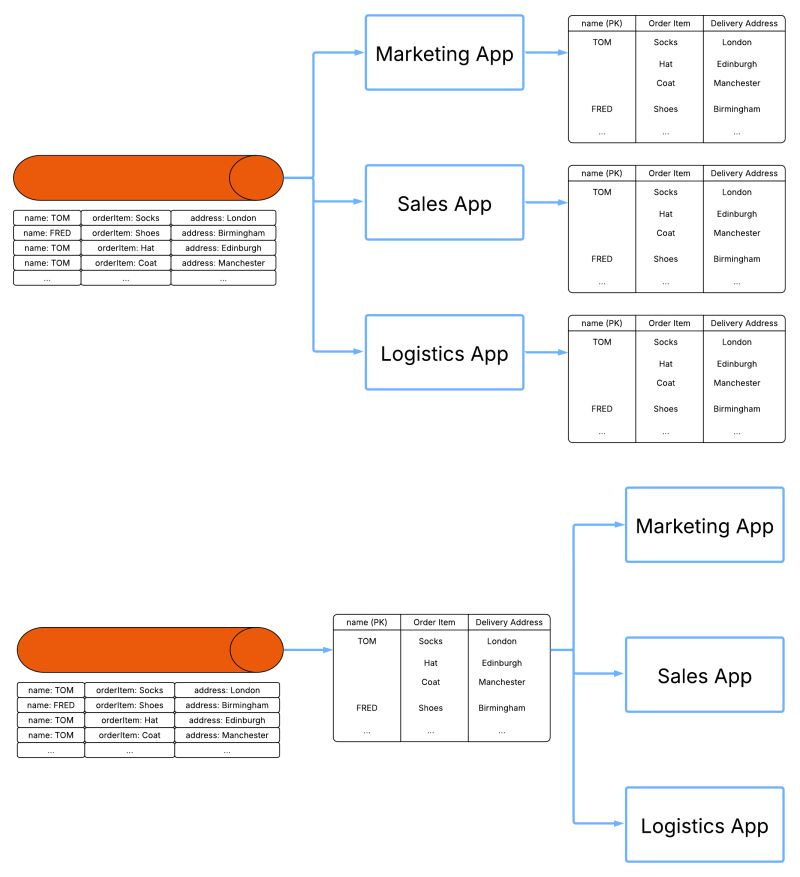

Traditionally, these materialisations are built directly into the streaming applications that use them. Applications individually load source Kafka topics and materialise stores for their use and their use only. If you have 3 applications that need the same store that’s 3 duplicate copies of the data. This is in direct contrast to database style indexing where indexes are built once and available to all. Platforms like Flink and KSql went some way to address this inefficiency by treating all streaming flows as a single distributed application but it is still not common practice to reuse the materialisations of one flow in another.

Unlike in the database (where a database engine operates over all indexes), there is no component in streaming that ensures materialised tables are consistent, not duplicated and optimized for the tasks they perform across all applications. The result of this missing component we call “index fan out”: a new pipeline, a new sink, a new copy of the same data for every materialisation and no consistency guarantees between them.

How can we address this limitation? By centralising the index. Creating a single authority for what is indexed where. All we need is a central place to store this indexing data: enter Iceberg. The ideal open and central place for applications to source from.

Fan-out indexing isn’t evil, it’s a workaround for missing primitives and a central management component. As logs and tables converge, the opportunity arises to stop duplicating data and start indexing it properly.

Part 4: Deduplication

On our path towards turning the database inside out there’s an elephant in the room that it’s finally time to confront: data duplication between streaming and analytical systems.

In a typical modern architecture, data lands in a streaming system, then gets ETL’d into an analytical store. Streaming applications read one copy, analytical applications read another and a multi billion dollar industry has grown up around transferring between the two.

However, by taking this approach we’re not just moving bytes around, we’re creating two (or many more) versions of reality. One might be a few seconds behind. One might have a slightly different schema. One might silently drop a field or re-order events. And now every downstream team has to ask the same uncomfortable question: which one is correct?

What if the problem isn’t ETL, but the boundary we’ve chosen?

Instead of treating streaming and analytics as two separate worlds that must be synchronized after the fact, imagine storage being composed of two parts: one optimized for streaming access and one optimized for analytical access. On top of that, a shared abstraction lets applications interact with the data without caring where a particular read or write is physically served from. This is the principle Streambased is founded around.

Earlier in this article I wrote about consuming WAL and long term storage elements of data architectures and it is these that create this composed dataset. In our inverted architecture Kafka provides the WAL element and Iceberg the long term storage. These are joined for analytical purposes by Streambased I.S.K. This lets analytical systems query live streaming topics as if they were just another set of tables, giving teams immediate access to the freshest data alongside full history in one place. All without ETL, duplication, or lag.

But what about streaming? This idea works in both directions, if we can compose storage for analytical workloads, why can’t we do the same for streaming workloads? That’s where Streambased K.S.I. comes in, instead of forcing Kafka clients to live only in the kafka data and leave the cold, analytical data unreachable. K.S.I. maps Iceberg’s rich historical store back into a Kafka-like interface so streaming systems can see the full timeline as a single, logically continuous topic.

Turning the database inside out again

To really “turn the database inside out” we need to stop thinking of Kafka and Iceberg as two separate destinations, and start treating them as two layers of the same logical system. Kafka is the hot edge: a fast, append-only WAL optimized for fan-out and low-latency consumption. Iceberg is the durable core: a table abstraction over cheap object storage that makes history queryable, evolvable, and governable.

The mistake the industry made was assuming the boundary between these two layers should be crossed with ETL, rather than bridged with database primitives.

Once you accept that, indexing and caching stop being “features of downstream systems” and become shared infrastructure again. Meaning:

A translation layer can project the log into the table, preserve locality, and expose secondary indexes as first-class assets rather than bespoke application code.

Materializations can be built once and reused everywhere, with consistency guarantees that feel more like a database than a pipeline zoo.

A single source of truth dataset can be consumed by operational and analytical clients in the formats they expect

In that world, the question isn’t whether Kafka replaces the database or Iceberg replaces the warehouse. The real shift is that the database becomes a set of open, interoperable components (log, cache, indexes, and tables) and we get to assemble them without giving up correctness or performance. Kafka was the start of the inversion, adding Iceberg makes it permanent. And the missing bridge between them is where the next decade of data infrastructure will be built.